As her youngest of two daughters recovered in a hospital bed at home following a horrific car wreck, Ava Welborn began feeling ill herself during the long hours by her child’s side.

“Ava would go eat and then throw up,” said her husband and Courtney Welborn’s dad, Danny Welborn. “We attributed it to the stress, because we were providing 24-hour care for Courtney. I finally got to the point where the day before our anniversary, I said, ‘I don’t know what’s wrong with you, but what you’re going through is not normal.’”

A hematologist at a Jackson hospital took about a week to diagnose Ava Welborn with a blood disease, but wasn’t satisfied and recommended she get a second opinion from a specialist at the University of Mississippi Medical Center. She saw now-retired hematologist Dr. Joe Files, received blood tests and got an almost instantaneous diagnosis: Acute myeloid leukemia, an aggressive blood cancer that is usually lethal if left untreated.

She began chemotherapy, a standard protocol, but her care team “immediately started talking about a bone marrow transplant,” Welborn said.

“I was afraid that I wouldn’t be able to participate in life as fully as I wanted to. I knew my husband would have to take care of me, and I didn’t want that,” Welborn said of her diagnosis at age 46.

“I asked Dr. Files, ‘Am I going to live to have grandchildren?’”

As the Medical Center celebrates the 30th anniversary of the state’s sole program providing bone marrow transplants to patients of all ages, Welborn and her family are grateful as she approaches the 20-year milestone of her June 2003 transplant. She’s in great health. She has two grandsons.

Welborn’s story “is the reason we do transplant,” said Dr. Stephanie Elkins, one of the hematologists who treated Welborn. “We want people to survive that long. People who have a transplant are usually high-risk, and even with a transplant, survival can be a roll of the dice.

“We want to prolong life and to increase quality of life,” said Dr. Dereck Davis, assistant professor of pediatric hematology and oncology. “We want to give these children extra years of life that they wouldn’t have otherwise.”

Since its program began in 1992, UMMC has performed more than 1,700 bone marrow transplants, BMT for short, now averaging about 75 a year, with an average 15 of those pediatric. Optum, a transplant insurance network, gave it national recognition it in April 2022 as a Center of Excellence.

BMT at the Medical Center got its start largely due to one man: Dr. Joe Files, who directed the Division of Hematology for 17 years. “He was one of the physicians who was leading the pack,” said Pam Farris, the BMT nurse manager who has been with the program since 1994. “He studied and trained at Fred Hutchinson (Cancer Research Center) in Seattle. That’s where they were actually developing the new science of bone marrow transplant.”

UMMC’s adult BMT physicians include two from the very beginning: Dr. Carolyn Bigelow, professor and medical director of BMT, and Elkins, professor and division chief of the Department of Hematology and Oncology. Other adult BMT team members are Dr. Carter Milner, associate professor of hematology, and Dr. Vince Herrin, professor of hematology. The pediatric team includes Davis and Dr. Jennifer Cox, associate professor of pediatric hematology and oncology.

Bigelow, Elkins and Herrin performed external rotations, and Milner an internship, at Fred Hutchinson, where BMT was pioneered in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Most patients are candidates for BMT because they have an aggressive blood and bone marrow cancer such as acute myeloid leukemia. In that particular leukemia, unhealthy leukemic cells grow and reproduce, crowding out or suppressing development of normal cells and progressing rapidly without treatment.

Children with sickle cell disease are among the average 10-12 annual pediatric transplants at UMMC, Davis said. “Mississippi has one of the largest sickle cell populations in the country. That puts us at the forefront of the ability to transplant these patients.”

Patients of all ages need normal, transplanted stem cells to replace the abnormal cells. To prepare for a transplant, patients typically receive chemotherapy. The goal is to get the patient into “remission,” meaning the chemo kills the bone marrow to kill the cancer.

There are two types of BMT: allogenic transplant uses healthy blood stem cells from a matching donor; autogenic transplants use a person’s own stem cells that are collected and frozen until use.

Two of the four people who received BMT at UMMC in 1993 are living today. Over the past 25 years, the risk of dying from transplant complications has dropped nationally from 30 percent to 11 percent. Even so, BMT is a serious procedure, and the first year can be fraught with complications and the possibility of rejection.

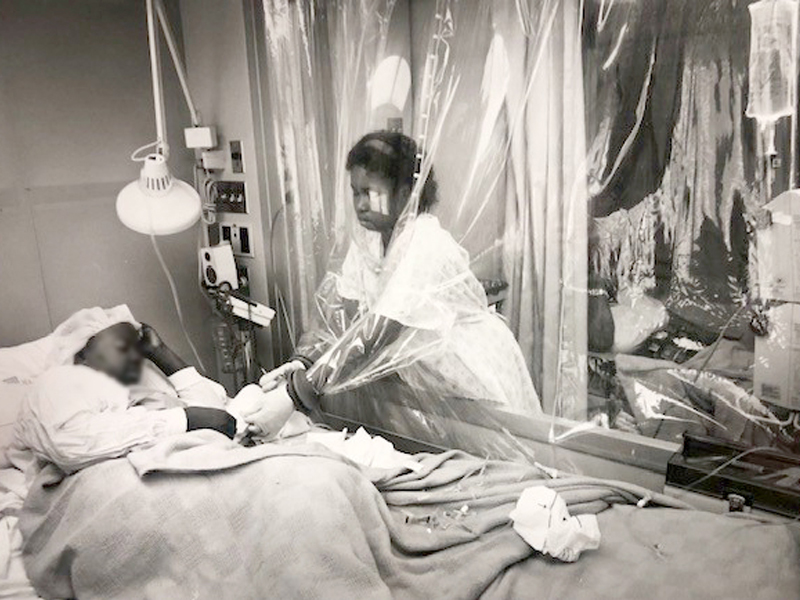

Files recruited Bigelow from Fred Hutchinson in 1988 to establish the BMT program from scratch. BMT looked drastically different then from today’s transplants that can be done intravenously at a patient’s bedside. The first clinical area at UMMC was two tiny, retrofitted rooms on 5 East that had laminar airflow, or a system that provides continuous, contamination-free airflow.

“The patient was behind a see-through plastic curtain with arm holes. We would stick our arms through to examine the patient, and if we went into the room, we had to dress out, just like going into the OR,” Bigelow remembered.

“We would take the donor to the OR, put them to sleep and do 150 to 200 sticks in the low back and pelvic region to get the bone marrow.”

Today, 12 beds on the fifth floor of the Conerly Critical Care Tower are dedicated to adult and pediatric BMT. “The entire floor is laminar airflow for sterility,” Bigelow said.

Patients and donors now spend four to six hours in a dedicated apheresis lab, hooked to a machine via an IV line in their arm that captures stem cells in their blood, then returns the blood into the opposite arm.

BMT is no longer considered just a treatment of last resort. “Today, you transplant to prevent things. It’s not always the major treatment,” Elkins said.

“My favorite thing about hematology is that we can do something as specialists that no one else in medicine can do,” Herrin said. “We harvest and transplant our own organ system. Even for a kidney transplant, you have to go to a surgeon to do it. Because stem cells are different, we do it all.

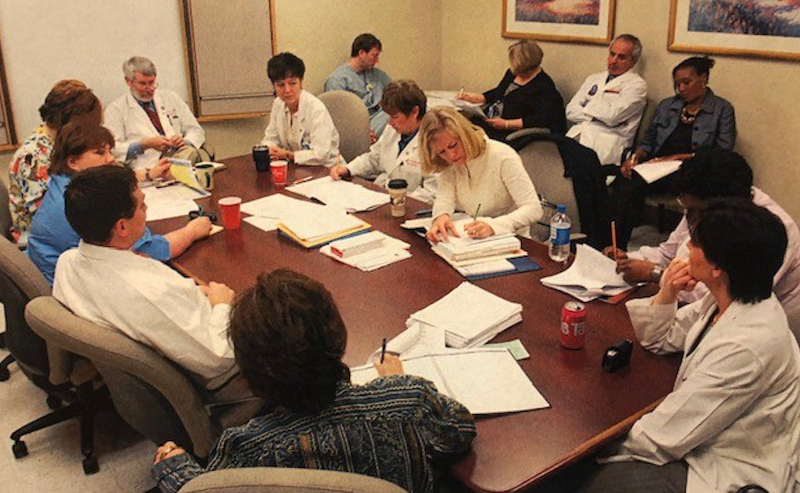

Just as the care of BMT patients is a team effort, so is the selection of who is a good candidate.

The cases of patients being evaluated, those approved and being prepared for the procedure, and those who are post-transplant are discussed by the BMT team during a weekly conference.

Providers speak frankly about each patient. What are the obstacles that stand in the way of transplant? Are the therapies working? Does the patient have a donor?

One patient matched to thousands of donors on the national donor registry – but the BMT team wanted to wait to see if an actual relative who was undergoing testing was a better match.

Donors optimally are between 18 and 55. The next patient discussed had two potential donors, one receiving a matching score of 10 out of 10. But the second donor, whose test results weren’t back, is younger than the first.

“With the age difference, I think it’s worth waiting,” said pre-transplant coordinator Jennifer Rouse.

The team made a difficult decision on a patient whose unrelated health issues kept them from passing a frailty test. The person had good support at home, a necessary qualifier for transplant.

“So, do we proceed?” Herrin asked.

“I think that’s appropriate. I think we proceed,” Bigelow said.

Another patient “regretted their family wanting them to go to MD Anderson, because they’re (Anderson) doing the same thing we’re doing here,” Herrin said. The patient “is tired of going to Houston.”

Scott Brumfield of Fayette, owner of a plumbing and septic tank business, in April 2021 got the disconcerting diagnosis of acute myeloid leukemia. Chemotherapy put the plumbing and septic tank business owner into remission, but he relapsed in June 2022 and the team approved him for BMT.

He received 10 days of chemotherapy on the BMT unit, then received an IV infusion of stem cells on Nov. 16 from his little sister, Katherine Foy of Natchez. “I love her to death for doing it,” Brumfield, one of five kids, said of his sister’s generosity. “She could have turned me down, but she didn’t.”

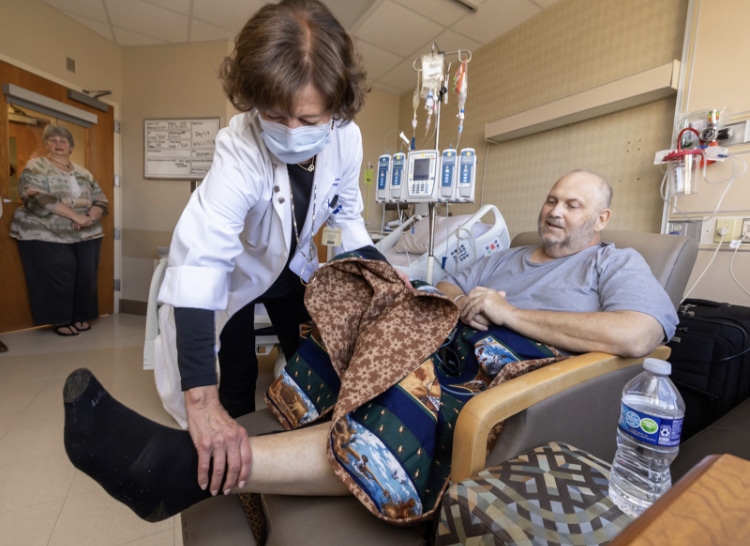

Brumfield’s care team visited him frequently to check how well he was regaining his stamina and appetite, scrutinize bloodwork and ask and answer questions. “Are you able to eat?” Bigelow asked when she rounded by his room Dec. 1. “You need right now 1,000 calories a day.”

“So-so,” Brumfield answered. He had been taking in sports drinks and liquid nutrition supplements, along with trying a Pop-Tart.

“Your white count is starting to come up,” Bigelow told him. “Those cells are in there growing.”

Brumfield’s wife, Jennifer, stayed by his side. “If someone doesn’t have a good caregiver, we don’t transplant them,” Bigelow said. “It’s a big process to go through, and you need someone to help keep you healthy.”

Brandon resident Cliff Russell received BMTs for multiple myeloma in 2013 and 2019. Today, he’s pursuing his pre-COVID passion as a volunteer in the BMT unit. Ava and Danny Welborn did the same thing for more than a decade after her BMT.

“My wife Linda and I start on one end of the floor and work our way through the patients,” Russell said. “We tell them that I had a transplant. We tell them what to expect, what to watch out for, give practical hints and answer any questions they have.”

“Watch what you eat,” he advised Brumfield. “Your resistance is about zero right now. If you get out in the yard, don’t get your hands in the dirt.”

Just as the science of BMT has evolved, so have the protocols, drug therapies and the chance of long-term survival.

“Our supportive care is so much better. We know how to prevent infections and disease for a lot of people,” Elkins said. “We know that people need to get up and move after BMT. Twenty years ago, we put them in a bubble room and they couldn’t come out the door.”

“We began looking at how we as a team can come together and better collaborate,” Milner said. “Keeping everyone in the same clinic, with the same people, has made a meaningful difference in patient outcomes.”

“We’ve gotten much smarter at looking at the patient and being able to say they can be treated with standard therapy, or instead we need to do a round of chemo, and then a transplant,” Elkins said. “We’re much better at predicting who will need a transplant.”

“The newest technology we want to get here is CAR T(chimeric antigen receptor) cell therapy. It has to be done at a transplant center. We are very capable of doing that,” Bigelow said.

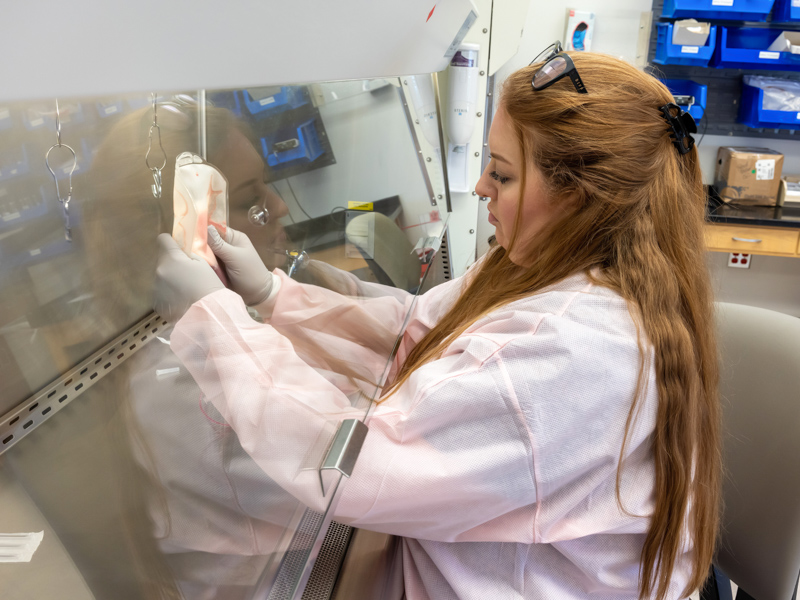

CAR T therapy involves taking T cells, a type of white blood cell, from a patient’s blood and genetically changing them in a lab to help them attack cancer. The cells are then transfused back into the patient.

Unlike 15 years ago, parents of sickle cell patients can now be their donor, Davis said. Children with sickle cell also can get a transplant from someone who’s a half-match.

Milner often thinks of the young mothers with high-risk leukemia. “Giving them another chance at long-term survival is a privilege. It’s incredible. It’s much bigger than ourselves.”

BMT “is a very complicated process, and you don’t do that without good people,” said Files, who worked full-time at UMMC from 1979-2011. “I was fortunate to have good people around me.”

Under the leadership of Bigelow and Elkins, Milner said, “we’re hitting our stride, and we’ve had great outcomes.

“We are as good as any of the states around us.”