Maybe it’s because we celebrated Memorial Day just a few weeks ago.

Maybe it’s because we recently observed the 80th anniversary of D-Day.

Maybe it’s because I just completed the striking novel, The Women, by Kristen Hannah, (more on that later).

Maybe it’s because the Fourth of July is upon us.

Combining all the above, and probably some other reasons as well, I’ve been thinking lately about my views on the Viet Nam War and its effects on the people who served in it and on our nation as a whole. For folks of a certain age, Vietnam was an emotional flashpoint in our lives. The Viet Nam War lasted, technically, from 1955-1975. The United States was primarily involved between 1964-1973. Those were the coming of age years for my generation .

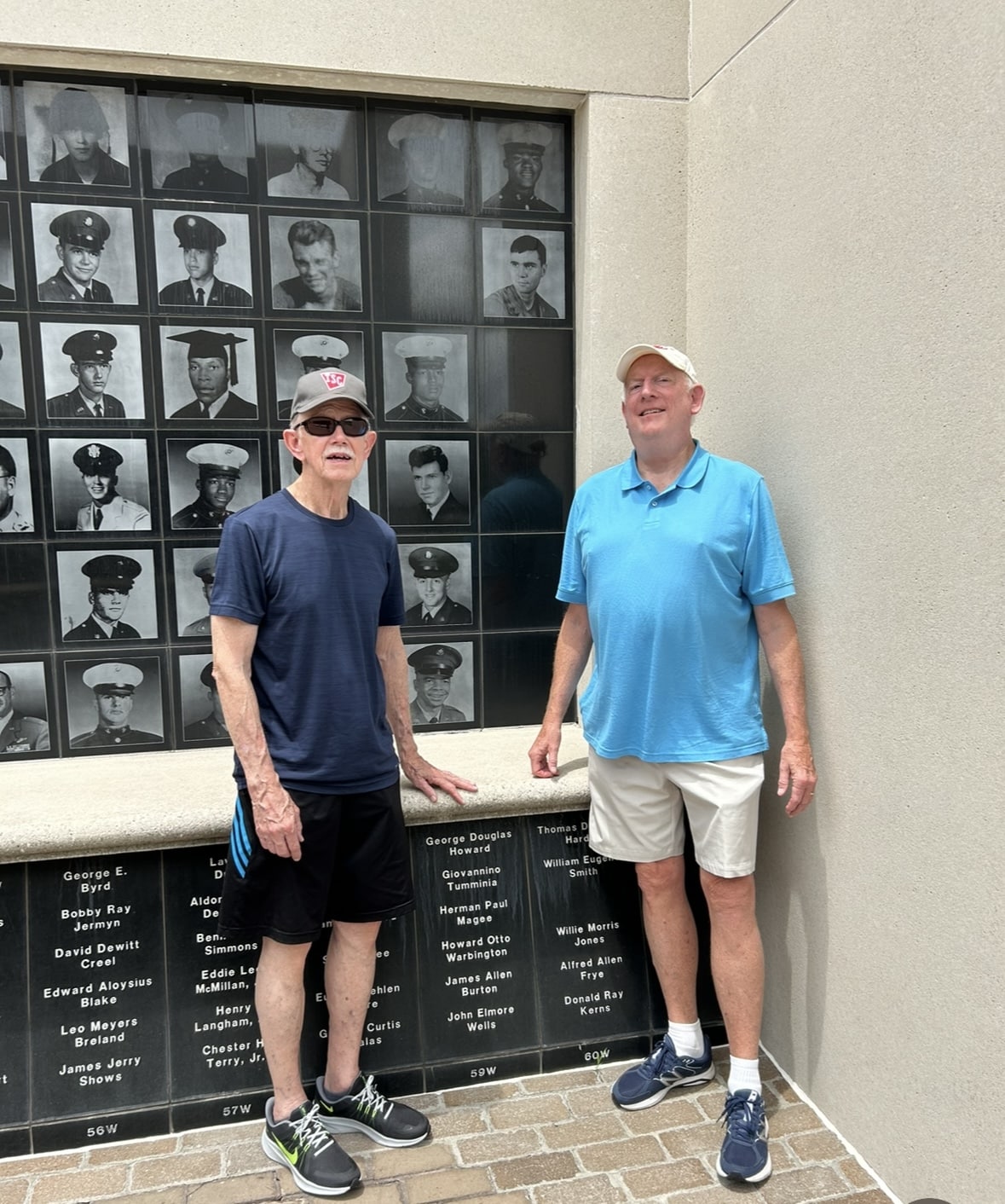

Today, I will highlight the two gentlemen closest to me who served in Viet Nam

The United States, sadly, lost 58,281 human beings in the Viet Nam War. One of them was William Eugene Smith, who graduated from Pascagoula High School with me in 1966.

Gene and I weren’t all that close, but we were good friends. We played a lot of sports together, particularly basketball, worked on school projects with each other, and rode up and down Market Street on the weekends.

When it came time for college, Gene and I had to take divergent paths. While I headed off to Ole Miss, Gene had to stay in Pascagoula and work, taking classes when he could at Mississippi Gulf Coast Community College (“JC By The Sea”, we called it).

See, I had more fortunate circumstance than Gene. I had supportive parents who could send me to college. Gene came from a background that, to be quite candid, was a bit tough and without a lot of financial means.

Gene was really bright, and projected to be very successful in college and in life. His goal was to save up money and eventually attend the University of Alabama. Back then, it was a big deal to write messages in each other’s yearbooks after graduation senior year. Gene wrote a really neat note in mine that said in part, “So glad you’re headed to Oxford. Next couple of years, I’ll be up at the Capstone, and we can visit back and forth”. (The Capstone is a sometimes nickname for UA.)

One time I came home from school and saw Gene at a movie theatre, working as a ticket taker. He would work any odd job he could, staying with his plan to eventually head to Tuscaloosa.

Trouble was, to keep a student deferment from the military back then, you had to maintain a certain amount of hours being taken at a college. Gene fell behind one semester, due to his work situation, and he was drafted and sent to Viet Nam.

Going in as a private in the infantry, Gene soon rose up in the ranks due to his intelligence, toughness, and leadership skills, and became a staff sergeant. One day, in May of 1970, as he was leading his platoon on a charge up a hill, he was shot and killed.

For a lot of us, that was a classic “there but for the grace of God” moment. Now, I’m not going to tell you that when Gene was killed a bunch of old friends got together and mourned, because that would be dis ingenuous. We were 21 or so years old, most of us in college. Our minds were on what classes to take next semester, how high our football teams were ranked, and where the next party was. When we talked, we said something like, “Man, I hate that about Gene”, shook our heads, then went on with our lives.

The years since have given us all perspective. I do think about Gene, and what he gave for our country, often. When he comes up in conversation amongst classmates now, it is with very appropriate reverence.

————————————————-

Earlier I mentioned the book The Women, by award-winning author Kristen Hannah. It is a superb historical fiction about women who served in Viet Nam as nurses, their experiences there, and how they were treated when they came home.

The principal character is the memorable Frances (Frankie ) McGrath, who was in country from early 1967until March of 1969. As I read the narrative of her journey, I realized that her time in Viet Nam coincide quite closely with that of my friend Johnny Fryer, and that much information mentioned in the book reminded me of things Johnny has told me over the years.

John Wesley Fryer and I go all the way back to attending Sunday School and church as youths at First Methodist in Pascagoula. Coming up we played basketball together (seems like a recurring theme there), including a stint on the ninth grade team when we served as leaders of merriment on the bus trips. I can still here tough guy coach Doc Nelson hollering “Fryer! Lucas! Cut that crap out and start thinking about the game!”

After PHS—here we go again—I went off to Oxford and Johnny headed off to the U.S. Army and Viet Nam. When he returned home, we reconnected at church and have been big buds ever since.

I asked Johnny if he was comfortable working with me on this column, and he graciously agreed. Herewith is a condensed transcript of the Q&A we did. I found the exchange fascinating, heart rending, and revealing, and I believe you will, too.

RBL: Why did you decide to enlist.

JWF: I was undecided on my career path. I knew my parents could not afford the cost of college. So, I took the path that would pay, shelter, and feed me until I could find my way in the world.

RBL: Talk briefly about your experiences in combat.

JWF: If you have ever read about “the Fog of War”, all of this comes to reality in the first few days of being in the jungle. The sound of the crack of being shot at and being disoriented in so many ways. A banana tree is not much cover when you need it.

The color of the jungle—the color green comes in so many shades. The nights are the darkest I have ever experienced. Then you realize how you can see so many stars in the heavens. Sleeping with an M-16 has to rank high on the memory scale.

RBL: What were your thoughts about home while you were over there?

JWF: You thought of home daily because everyone talked about their home. My red GTO was on my list, and, of course, family. At every meal time I thought of Edd’s chili-cheese. Last but not least, the scent of a woman. Why, because the smell that was so prevalent was that of rotting jungle vegetation.

RBL: Talk briefly about assimilating back to “normal” life when you came home after mustering out.

JWF: After returning to the “world”, as we would say, you had to get used to sound differently. Sounds had a totally different reaction. We had to also get used to all the anti-war demonstrations that were everywhere. Your uniform gave you away immediately. You had to take a different route in an airport or have a cab driver refuse to take you anywhere.

RBL: Any final reflections about serving in Viet Nam?

JWF: So many of the military came home with PTSD. Some of the scars will be hidden forever. Others will rise to the surface, and for those folks, we pray they will get help. Others say that we were “just at the wrong place at the right time”.

Wow. Just wow. Doing that session with Johnny just shook me to the core. We’ve talked about his Viet Nam experiences off and on over the years, but just compacting these questions and responses was powerful. I’m not sure what was most troubling to listen to—obviously the combat stories, but also hearing about how the vets were treated on returning home. You just don’t havethe exact words to express how you feel upon walking through a Viet Nam vet’s experiences—especially a friend’s—as a moment in life most of us will never know.

Gene Smith, 25th Infantry Division, A Company, received the Bronze Star, Medal For Valor, and the Purple Heart for his service in Viet Nam. John Fryer, 4th Infantry Division, C Company (and, like Gene, eventually a sergeant), was in country for 358 days, and received the Combat Infantry Badge, the Purple Heart, and two Army Commendation Medals. Bravo and bravo.

Putting this column together was mentally taxing (poor me), because of all the emotions it evoked and the reflections it has caused. Again, the Viet Nam War will always hold a special, dark space in the memory bank of many of us, especially my generation. On these pages, I just wanted to share with you my thoughts about two good Pascagoula guys who experience Viet Nam first hand. Thanks, Gene. Thanks, Johnny.

Richard Lucas may be reached at [email protected].