Research into the chemical composition of pottery shards taken from archeological digs in the Holy Land by Mississippi College faculty and students has revealed significant social networking and trade routes that verify certain accounts contained in the Bible.

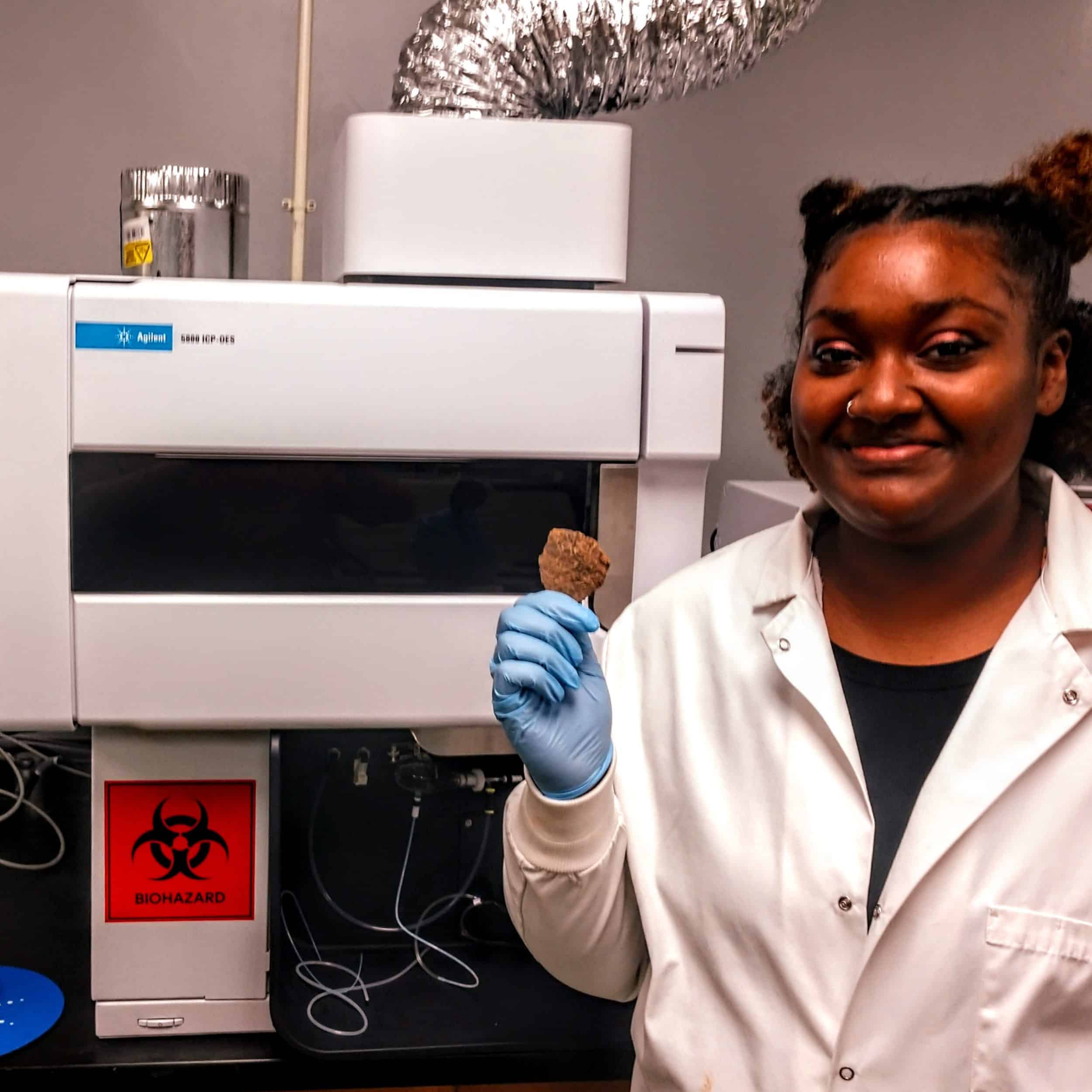

Using state-of-the-art inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) equipment, students in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry at MC analyzed the elements contained in each of the samples from throughout Israel and Corinth, Greece.

They discovered ceramic pottery from such places as Jerusalem, Jericho, Masadah, Herodium, Timnah, En Gedi, Bantas, and Hazor display the same, distinct characteristics, confirming that trade and cultural exchanges took place between merchants and residents of these cities.

Scoty Hearst, assistant professor in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry and Environmental Chemistry Team leader, said the findings indicate strong social connections between these ancient civilizations that bring the truth of the Bible to life.

“We hear about all these places in the Bible, so it’s neat to see that there were social and trade routes between them,” Hearst said. “It brings the stories about Samson and Delilah and King Herod home and makes them more real.

“It’s great to use chemistry and science to support our Christian beliefs.”

According to the Old Testament book of Judges, God gifted Samson with incredible strength to serve as a judge in the nation of Israel. He hated the Philistines, who had oppressed Israel, and fought them single-handedly. Nevertheless, he fell in love with a Philistine woman named Delilah. She betrayed the source of his strength to Philistine rulers, who, with Delilah’s help, captured and blinded him. God forgave Samson, who rallied to destroy the temple, freeing the Israelites from Philistine rule.

Hearst’s team studies some of the pottery samples from Zorah, Samson’s birthplace, and Timnah, Delilah’s hometown. Both cities were situated along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea.

“Timnah is where the Philistines were, and Zorah was where the Israelites were,” Hearst said. “There was a major trade route going all the way from Greece into Timnah, then on to Jerusalem. There were probably ships sailing the Mediterranean bringing pottery and other goods, and even though they were different religions, they would still trade with one another.

“That may be how Samson and Delilah met, along this trade route. You could see how Samson could have seen Delilah and fallen in love with her. They weren’t supposed to marry each other, but where there was trade, people socialized. It is evidence that this Biblical story isn’t just a story, but has historical roots.”

Another historical figure mentioned in the Bible is Herod, who was king of the Jews at the time of Jesus’ birth. The Gospel of Matthew records that, upon hearing from the wise men that a new king had been born in Bethlehem, Herod decreed that all male infants under the age of 2 in that town be slaughtered. An angel appeared to Joseph in a dream, warning him to flee Bethlehem with Mary and the infant Jesus. Herod is also known for his colossal building projects throughout Judaea.

Hearst’s team studied pottery samples from three cities ruled by Herod: Herodium, Masadah, and En Gedi.

“The pottery was very similar,” he said. “That makes a lot of sense, because that’s where he was ruling at the time. There would have been much trade between the cities he was occupying.”

Archeologists value pottery because its characteristics provide concrete evidence of shared culture and cultural exchange, such as ideas and trade. Over time, other evidence of a civilization may disappear, but its pottery gives historians a dependable tool to study its way of life.

“Pottery gives you a view of an area’s culture and social connections,” Hearst said. “There were probably dozens of pottery kilns across the Holy Land. People used it every day. It could have religious significance if made into an idol, or used for cooking and storing wine, certain rituals like washing your feet, or storing certain oils.

“There’s a certain recipe to making pottery that is passed down from generation to generation, and the chemical composition will be indigenous to the area where the clay was harvested. You could see how a potter from one town could sell or trade his pottery in the next town, and then it would get sold or traded from there.”

The MC study took more than four decades to complete. It began when Dr. Dean Parks, professor emeritus of chemistry, and his wife, Barbara, traveled to the Holy Land on two occasions in the late 1970s to participate in certified archeological digs.

“We went with an MC student who wanted to analyze soil samples to establish population density,” Parks said. “As you dig into the earth, it’s like going through the layers of a cake – you have a layer from one age, then you go deeper and find a layer from an earlier time. Occasionally, you can see a layer that is all black, where a fire has burned everything down.

“For different ages, the potters had slight differences in the way they designed and decorated their pottery. After the archeologists had examined what they had found in the digs, many of them threw away the pottery shards. That’s where most of these samples came from. When we collected them, there wasn’t an easy way to analyze them, so I kept them.”

The samples Parks contributed to the study encompass the Biblical time period stretching from the early Bronze Age to the later Roman empire. Parks said he was pleased to find a useful purpose for the shards he had stored for decades.

“It’s a great satisfaction to have something positive come out of the work done decades ago,” he said. “Of course, those decades are just a fraction of the lifetime of that pottery. I was pleased to be able to help Scoty and the students who were working on the project.”

The process for determining the pottery’s content is destructive: students grind up the samples, digest them with acid, filter them, and feed them through the ICP-OES analytical tool. The instrument can detect and measure all the elements of a sample, including carbon, lead, sulfur, calcium, magnesium, and aluminum. MC recently acquired the machine for the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry.

“It’s the newest instrument and among the best equipment used in the industry today,” Hearst said. “It demonstrates the expert level of our department’s chemical analytical capabilities, and the high quality of training our students can receive.”

Hearst’s group measured the amount of 17 elements present in the pottery samples to determine their unique characteristics. These characteristics were compared with those of other samples to yield a similarity score that could authenticate whether they had any relational value. The students developed a Social Network Analysis that connected cities with similar pottery, producing a “spider web” of the trade from Greece throughout the Mediterranean.

“If they shared common characteristics, we can assume they came from similar pottery kilns, or they were made from similar clay, or they were decorated with similar paint,” Hearst said. “If you had pottery made in one location and traded all over the Holy Land, you would find pieces of that pottery everywhere.

“In cities that were closer together, the pottery matched. Greece is not close to the Holy Land – it’s across the Mediterranean – but the pottery from Greece closely matched the pottery shards from Jerusalem and Timnah. Jerusalem was a large city, so it would have had a lot of trade with foreign nations like Greece. It was neat to see that evidence.”

As a control, the students also ran samples from Native American pottery and pottery collected from the Crusades period. Neither matched the pottery from the Holy Land.

“It shows our scientific technique for looking at the chemical composition of this pottery was valid,” Hearst said.

Students who participated in the study enjoyed discovering a direct connection to the Bible. Takaye Farmer, a senior chemistry major and Spanish and physics minor from Memphis, said the opportunity to see pottery from the Holy Land attracted her to the study.

“Being able to work with and analyze pieces from such a long time ago was fascinating to me,” said Farmer, who presented the project at the Southwest Regional Meeting of the American Chemical Society last November. “Because all of the samples we received were fragments, it was interesting to wonder what kind of pieces they may have come from.

“Many of the trade routes and social connections we discovered correspond with places and stories in the Bible.”

Lexi Harris, a senior chemistry, medical sciences, and English writing major from Carthage, said the study appealed to her sense of history.

“I have learned how simple pieces of clay can open up doors to the past to answer our own questions,” said Harris, who is scheduled to present the project later this month at the Mississippi Academy of Science Conference in Biloxi. “The findings might help archeologists pinpoint certain aspects of the Bible, should they choose to use our findings.”

Hearst said the study has drawn attention from the scientific community as well as art galleries that conduct chemical analysis on treasured pieces to show the science behind the art.

“What’s interesting about the pottery is you don’t know who might have had it,” he said. “Samson could have eaten from or drank from this vessel. Just holding a piece of the Holy Land in your hand makes it more realistic.

“It’s great for students’ education. We are a Christian college, and it’s exciting to merge our beliefs and science to show that the Bible is truth. Now we have more scientific evidence to prove it.”