One of the most historical roadways in Mississippi is the Natchez Trace, and this is the perfect time to venture on to arguably the most beautiful stretch the state has to offer. With some people off work this week and a slight nip in the air, there’s no time like the present to go on a joyride and the Natchez Trace is the place to do it. Before you go though, there are a few facts you might want to know about the 444-mile scenic drive.

History of the Natchez Trace

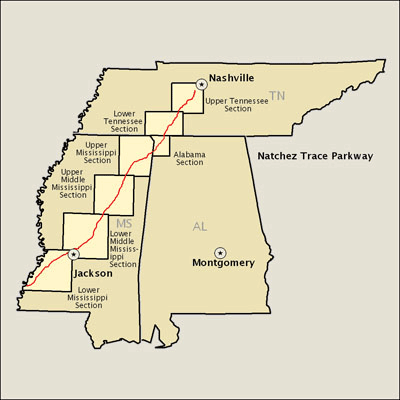

Filled with wonder, intrigue, battles, and mystery, the history of the Natchez Trace makes it that much more worth visiting. Formerly known as the Old Natchez Trace, the roadway starts in Natchez, Mississippi, before going through the top corner of Alabama and ending in Nashville, Tennessee.

Dating back to prehistoric times, giant creatures grazed along the lands by the Mississippi River leading to the salt licks located in middle Tennessee. Following the footpaths of these deer, bison, and other large game, the Native Americans began marking off what today is the Natchez Trace.

Leading the charge for the Natchez Trace, Native Americans had settled the land and helped improve it into a more established pathway. There are many prehistoric indigenous settlements marked by a monument, park, or something of the sort. Some of the locations are estimated to be over 2,000 years old.

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the trail was taken over by European and American explorers, traders, and emigrants. They used the trail for lodging inns as well as a good area to search for food before the steamboats took over transportation along the river.

The first explorer to have been recorded traveling the trace was an unnamed Frenchman in 1742, describing its “miserable conditions.” Early Europeans enlisted the help of Native Americans, mostly Chickasaw and Choctaw, to guide them through the area since they knew it well. Within no time, the Natchez Trace had become a major location for trade in the countryside. Chickasaw leader, Chief Piominko, made great use of the trail, and it was known as Piominko’s Path during his lifetime.

Well before the development of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, President Thomas Jefferson sought to connect the vast Mississippi frontier to other settled areas across the U.S. The Chickasaw and Choctaw tribes signed treaties to maintain peace as an influx of Europeans flooded in. In 1801, the Army took over construction along the trace, turning the trail into a major thoroughfare and named it the Columbian Highway.

A darker period then set in as the highway became a major center for crime. Often referred to by travelers as “The Devil’s Backbone,” large portions of the road consisted of rough and remote conditions and many times, travelers were met as unwelcomed guests. History shows that highwaymen would hide among the desolate areas, bringing destruction and fear as they stole possessions, killed travelers, and even captured and enslaved many.

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the “Great Awakening,” a series of religious revivals in the American Christian movement, made it to the Natchez Trace. Due to the lack of ministers in the area, many of the Methodist preachers formed a circuit to offer their services in the area. They were soon joined by other Protestant denominations including Baptist and Presbyterian. The Presbyterians included a migration of Scots Irish and Scots into the frontier countryside, and the most active branch of the religion in the area was the Cumberland Presbyterians.

With the development and migration of some people and locations, the crime level rose as well. Much of the banditry occurred around the river landing located near the Natchez Under-the-Hill. It was the target of more villainous behavior than the rest of the town that was located atop the river bluff. As barges and keelboats unloaded their stock of goods from the North, the area soon became a redlight district for gamblers, prostitutes, and drunken crewmen. Many of the “Kaintucks,” the rapscallion frontiersmen from Kentucky often lost their paychecks, gambling at the Inn. They were forced to walk or ride horseback the 450 miles back to Nashville. It was estimated in 1810, over 10,000 Kaintucks used the Trace quite regularly for their next load down the river.

In the area outside of the city, there were other great dangers that travelers and workers had to contend with. Highwaymen, and gangsters, such as John Murrel and Samuel Mason, tormented and terrorized travelers on the road. The Highwaymen created large groups of organized brigades in one of the first forms of land-based organized crime in America.

From the late 1790s to the 1840s, inns — known as stands in those days — lined the Natchez Trace, offering lodging for weary travelers. The stands gave the men a place to rest, prop up their feet, and catch up with the local news. They were furnished with food and accommodation, meager as they were, while they were updated on the latest news, information, and new ideas that were floating around across the country. Even though the accommodations and food were not plenty, consisting of corn hominy, bacon, eggs, biscuits, and coffee with sugar and whiskey, the men devoured the food like they were at the finest restaurant around. The lodging was not grand, consisting of only a few beds for the travelers to sleep on or searching for a spot on the floor or the outdoor porches, the travelers did not complain and were thankful for a small place to rest.

While traveling on the Natchez Trace, Meriwether Lewis of the Lewis and Clark Expedition died as he was traveling from Louisiana Territory where he was governor onto his way to Washington, D.C. Lewis sought shelter at Grinder’s Stand for an overnight stay in October 1809. Lewis was a troubled man and was dismayed over many issues. Brought on by his use of opium, it was believed that Lewis committed suicide with a gun. There was much dispute whether the death was by suicide or murder, Lewis was laid to rest near the Inn. On the bicentennial of his death in 2009, the first national public memorial service was held honoring his life.

Another marker that you shouldn’t miss if you travel to the Natchez Trace is located on an oddly shaped piece of land where a few signs, exhibits, and shackles are cemented in the ground. From 1833 to 1863, the area received the name of Forks of the Road. As the largest slave market in America, local historians, residents, and officials recognized this land as a new “national historical park site.”

It was here that tens of thousands of enslaved men, women, and children were auctioned off to work in the fields and plantations. It became such a crucial feature of the national economy, as many of the Natchez residents soon became millionaires. There are future plans to build an educational visitor center and a monument on the 18.5-acre site.

“History is not always pleasant, but it’s important that history be told, all of it,” Natchez Mayor Butch Brown said at the time.

Many of the descendants of the African-Americans who worked on or lived on the surrounding lands still call Natchez home today. It was important for the city to recognize all the contributions of all the people in the history of Natchez. To truly understand history, all sides of the story should be represented.

Whether you’ve visited the Natchez Trace many times or you’re planning your first trip there, we’ve got ten interesting facts filled with ghostly tales, mystery, and a view into the past that you shouldn’t miss out on.

- The Meriwether Lewis Monument—Find this gravesite where Lewis was laid to rest, and it is still argued to this day whether his death was the result of suicide or murder.

- Full of evil, spiteful Highwaymen roamed the trail. It is even said that Joseph Thompson Hare buried his unfaithful mistress alive somewhere near the trail. Until he was hanged for his crimes in 1818, Hare was haunted by “the vision of a phantom white horse.” It’s even said that on foggy nights, the trace takes on an eerie glow and there can be heard the cries of a young woman.

- Known as “Old Hickory” due to his strong determination and old hickory walking stick that he carried everywhere he went, U.S. President Andrew Jackson led his troops down this precarious route during the War of 1812. Jackson Falls at milepost 404 is named in his honor.

- There are still disputes about whether the Natchez Trace was actually formed by heads of bison seeking out salt licks near Nashville, but you can take a look yourself and make your own decision.

- Others credit the formation of the Natchez Trace and the leaders of the area’s 19th-century traffic of the Kaintucks.

- Look for Milepost 423.9. It is known as the Tennessee Valley Divide. In 1796, this was known as the southern border of the United States and the Chickasaw Nation comprised the Southern area.

- Pharr Mounds, located at milepost 286.7, is the gathering of eight ancient burial mounds dating back approximately 2,000 years. This trading hub was an active location during this time.

- Located at Milepost 107.9, the West Florida Boundary is land administered in part by France, Great Britain, and Spain. The rebels in this part of the territory were known as West Florida for 90 days in 1810.

- In 1742, the first recorded traveler ventured through the Trace, writing of the hardships of the trail and its “miserable conditions.”

- The Natchez Trace was first officially known as the Columbian Highway. The title, given by President Thomas Jefferson, ordered the expansion of the trail to build links to the distant Mississippi territory.

Plan your exciting adventure to the beautiful Natchez Trace today. Take in the beauty of the countryside and experience the locations where many prominent acts of history occurred in the early formation of our state and country. You’re sure to find many other ghoulish, ghastly, or interesting facts that happened along the Natchez Trace. It’s always a new adventure every time one ventures down this history trail.